Colonialism came to mind as I was listening to Dan Snow’s recent History Hit episode with author Sathnam Sanghera about how the British Empire is responsible for much of the modern world:

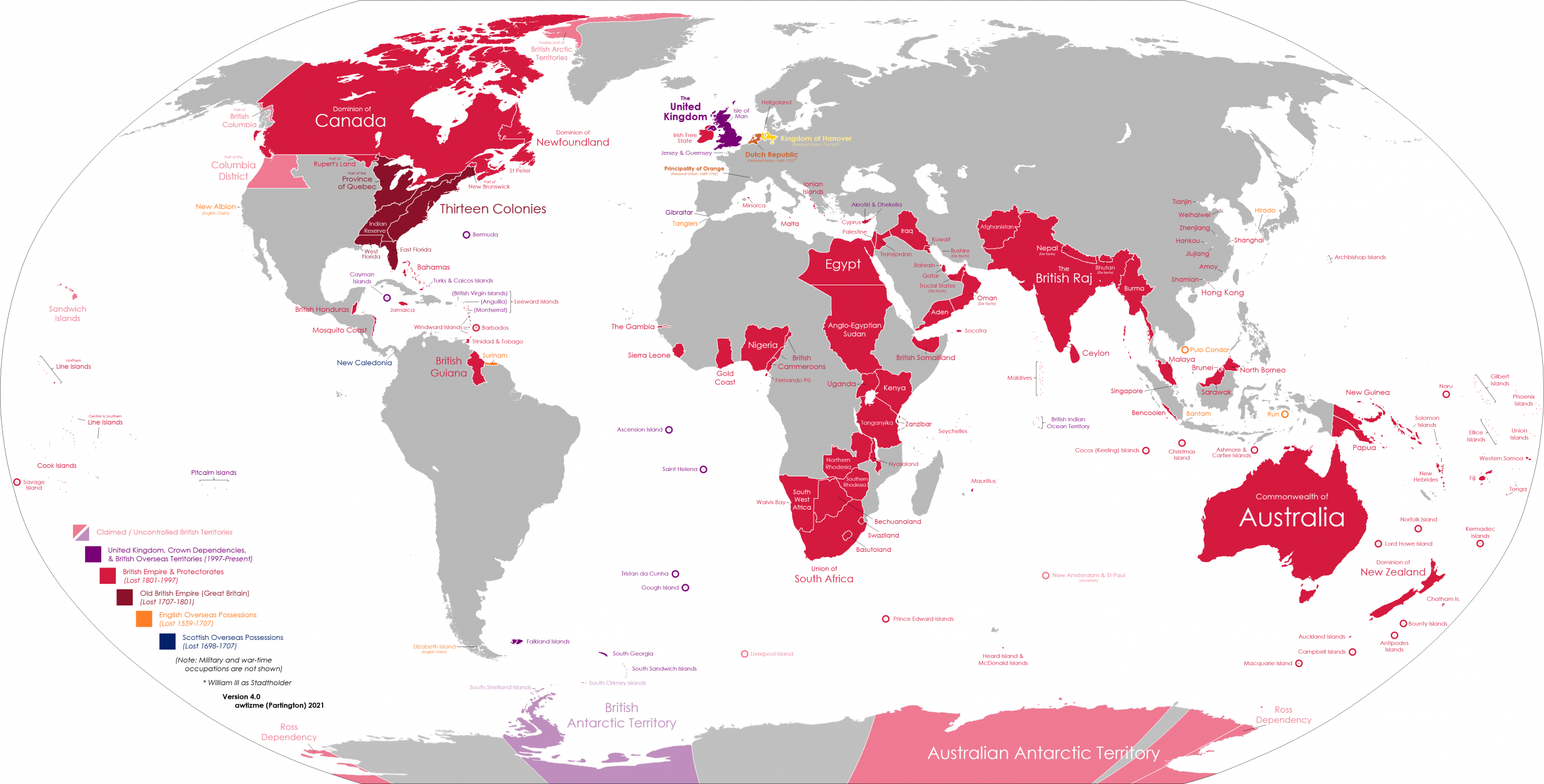

“Tobacco, sugar, rum, cotton, rubber, tea, coffee, spices, industry, borders, slavery, war – all things spread across the globe thanks to the British Empire. At its height in 1922, it was the largest empire the world had ever seen, covering around a quarter of Earth’s land surface and ruling over 458 million people- that’s a lot of influence. Dan is joined by journalist and author Sathnam Sanghera to measure the impact the British Empire has had on our world, for better and worse.“

They jokingly mention how the British are responsible for most of the modern conflicts due to people who didn’t understand or care about the regions drawing random lines on maps. This made me reflect on my own origins. I was born in Australia. My family has been here for a very long time (but not as long as many Indigneous folks). And it is all ‘thanks’ to the British.

I say thanks to the British somewhat ironically because I’m pretty sure my ancestors would’ve preferred not to come to Australia. One of my ancestors was not even a British national and yet he and his six compatriots were sentenced by the British as pirates and condemned to life in New South Wales. Some of my ancestors were sentenced to life in New South Wales due to stealing small items (but I expect they felt it was a better option than being hanged). Some of my ancestors came to Australia on ships fleeing the British induced famine in Ireland. But all of them coming was due to empire and colonialism.

My Greek ancestor who was sentenced for piracy to life in New South Wales and arrived on a ship in 1829, was pardoned in 1837 and he went back to his home place of Hydra in Greece. A few years later two of his sons came back here to settle. There must’ve been something in the stories he told them that made them think that Australia was a good place to settle in spite of the hardships that their father would have suffered as a convict.

I consider my lot in life to be a happy one to have been born in such a country as modern Australia. But there is no doubt that my current happy life here in Australia has been built on the suffering of the Indigenous peoples, and the suffering of the convicts who built this country. Life in contemporary Australia offers extraordinary comforts, such as access to healthcare and education, relative political stability, and the everyday freedoms that come with living in a wealthy, peaceful nation. Yet those comforts did not emerge in a vacuum – they rest on foundations laid by invasion, dispossession, and coerced labour. The land that enables this good life was taken from Indigenous peoples whose sovereignty has never been ceded, whose cultures were attacked, and whose communities still live with the consequences of policies designed to remove, assimilate, and erase. At the same time, much of the early physical and economic infrastructure of the colony was built on the backs of convicts who endured brutal punishment, forced labour, and profound separation from home and family.

For me holding that knowledge means accepting that personal good fortune is entangled with other people’s suffering, both historical and ongoing. It invites a more honest gratitude, and one that recognises unearned advantages, honours those who bore the costs, and asks what responsibilities flow from benefiting from a system shaped by colonial violence and exploitation.

Colonialism is often discussed in the abstract, but for me it lives in my family tree and the ground upon which I stand. The British Empire brought my ancestors here through punishment, desperation, and chance, and I have inherited both the privileges of modern Australia and the shadows of our history. Sitting with this, for me, means holding gratitude for the life I have, alongside sorrow for the suffering that built it, and a responsibility to acknowledge the ongoing impacts of invasion and dispossession on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Recognising that complexity feels like the smallest first step towards a more honest conversation about who we are, how we got here, and what we owe each other now.